Python Dictionaries

01.10.2018 — Programming — 13 min read

This article was originally posted on Python Pandemonium

Data structures are basically containers that store data in predefined layouts, optimized for certain operations — like apples in a box, ready for picking😉.

The Python programming language natively implements a number of data structures. Lists, tuples, sets, dictionaries are but some of them. We will be looking at the dictionary data type in subsequent sections.

What are dictionaries ?

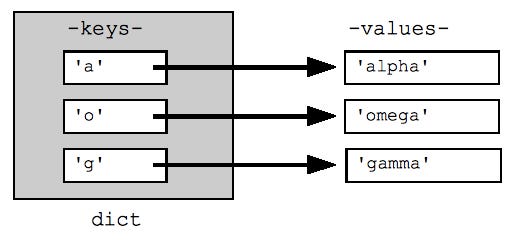

A dictionary in python is a mapping object that maps keys to values, where the keys are unique within a collection and the values can hold any arbitrary value. In addition to being unique, keys are also required to be hashable.

An object is said to be hashable if it has a hash value (implemented by a hash() method) that does not change during the object’s lifetime. Most commonly, we use immutable data types such as strings, integers, and tuples (only if they contain similarly immutable types) as dictionary keys.

A dictionary’s data is always enclosed by a pair of curly braces { }, and would normally look like this:

my_dict = {"first_name": "John", "last_name":"Snow", "age":16, "gender":"Male"}

We have created a dictionary named my_dict where each key-value pair is separated by a full colon, with the key-value pairs as:

-

first_name - John

-

last_name - Snow

-

age - 16

-

gender - Male

Typically dictionaries store associative data, i.e data that is related. Examples of such data include the attributes of an object, SQL query results and csv-formatted information. Throughout this article, we will be using dictionaries to store job listing details from Kaggle.

Comparisons

Dictionaries are an implementation of Associative Arrays. All Associative arrays have a structure of (key, value) pairs, where each key is unique for every collection. Other languages also have similar implementations, such as:

-

Maps in Go

-

std::map in C++

-

Maps in Java

-

JavaScript objects

Unlike sequenced data types like lists and tuples, where indexing is achieved using positional indices, dictionaries are indexed using their keys. Therefore, individual values can be accessed using these keys.

Dictionary Operations

1. Creation

- We initialize an empty dictionary using a pair of curly braces. This approach is often used when we expect to store some data at later stages of our operation.

empty_dict = {}

In the line above, we have created an empty dictionary named empty_dict.

- For instances when we have our data beforehand, we use curly braces with the key-value pairs. We can now create a dictionary to represent the second row of data in the jobs.csv file.

>>> job1 = {"title":"Production Manager",

"location":"Rest of Kenya",

"job_type":"Full Time",

"employer":"The African Talent Company (TATC)",

"category":"Farming"}

We just created a dictionary with the keys title,location, job_type, employer, category and assigned it to the variable job1.

- Dictionaries can also be created using the dict() constructor. To do this we pass the constructor a sequence of key-value pairs. We could also pass in named arguments. Let’s create a dictionary to represent the third row of data in the jobs.csv file, using both of these methods.

# create an empty dictionary

empty_property = dict()

# create dictionary using a list of key-value tuples

job2 = dict([

("title","Marketing & Business Development Manager"),("location","Mombasa"),

("job_type","Full Time"),

("employer","KUSCCO Limited (Kenya Union of Savings & Credit Co-operatives Limited)"),

("category","Marketing & Communications")

])

We passed a sequence, in this case a list of key-value tuples, to the dict() constructor to create our dictionary, and assigned it to the variable job2.

# Using keyword arguments

dict(

title="Marketing & Business Development Manager",

location="Mombasa",job_type="Full Time",

employer="KUSCCO Limited (Kenya Union of Savings & Credit Co-operatives Limited)",

category="Marketing & Communications"

)

Here, we created a dictionary using named arguments. The keys are the argument names, while the values are the argument values. It is however important to note that this method is only suitable when our keys are just simple strings.

2. Accessing Items

As we mentioned earlier on, dictionaries are indexed using their keys. To access a particular value in a dictionary we use the indexing operator (key inside square brackets). However, to use this method, we need to make sure the key we intend to retrieve exists, lest we get a KeyError. Checking for availability of a key is as easy as using the in operator.

# Check existence of title

"title" in job2 # returns True

"salary" in job2 # returns False

# Using key indexing

job2["title"] # return 'Marketing & Business Development Manager'

-

In the example above we use indexing to access the title from job2 after making sure it is available using in.

-

If you are like me, this is probably a lot of work. The good news, however, is that we have a better tool — the get() method. This method works by giving out a value if the key exists, or returning None. None sounds better than an error, right? What if we want to go even further, and return something, a placeholder of sorts? get() takes a second argument, a default value to be used in place of None. Now let’s use in to check if title exists in job2, then we can use indexing to retrieve its value. We’ll also go ahead and use get() to retrieve salary from job2.

# Using get() method

job2.get("title") # return 'Marketing & Business Development Manager'

job2.get("salary") # return None

# Passing a second argument to get()

job2.get("salary", 5000) # return 5000

Here, we use get() to access the title and salary.

However, job2 doesn’t have a salary key so the return value is None. Adding a second argument, to get() now gives us 5000 instead of None.

3. Modification

Dictionaries can be modified directly using the keys or using the update() method. update() takes in a dictionary with the key-value pairs to be modified or added. For our demonstration, let’s:

-

Add a new item (salary) to job2 with a value of 10000.

-

Modify the job_type to be “Part time”.

-

Update the salary to 20000.

-

Update the dictionary to include a new item (available) with a value of True.

# Adding a new entry for salary using the index

job2["salary"] = 10000

# Modifying the entry for job_type using the index

job2["job_type"] = "Part time"

# Modifying the salary entry using update

job2.update({"salary":20000})

# Adding the available entry using update

job2.update({"available":True})

To add a new entry, we use syntax similar to indexing. If the key exists, then the value will be modified, however, if the key doesn’t exist, a new entry will be created with the specified key and value.

-

Initially, we assigned a value of 10000 to the salary key, but since salary doesn’t exist, a new entry is created, with that value. For our second example, the job_type key exists, the value is modified to “Part time”.

-

Next, we use the update() method to change the salary value to 20000, since salary is already a key in the dictionary. Finally, we apply update() to the dictionary, a new entry is created with a key of available and value of True.

A particularly nice use case for update() is when we need to merge two dictionaries. Say we have another dictionary extra_info containing extra fields for a job, and we would like to merge this with job2.

extra_info = {

"verified":True,

"qualification":"Undergraduate Degree",

"taxable":True}

# Merge extra_info with job2

job2.update(extra_info)

4. Deletion

We can now remove the just created salary entry from job2, and remove everything from job1.

del job2["salary"]

del job2["available"]

print(job2) #return a dictionary without 'salary' and 'available' entries

job1.clear()

print(job1) #return an empty dictionary

del job1

print(job1) # return NameError

To remove the entries associated with the salary and available keys from job2, we use the del keyword. Now if we go ahead and print job2, the salary and available entries are gone.

Removing all items from job1 entails using the clear() method, which leaves us with an empty dictionary. If we don’t need a dictionary anymore, say job1, we use the del keyword to delete it. Now if we try printing job1 we’ll get a NameErrorsince job1 is no longer defined.

6. Iteration

A dictionary by itself is an iterable of its keys. Moreover, we can iterate through dictionaries in 3 different ways:

-

dict.values() - this returns an iterable of the dictionary’s values.

-

dict.keys() - this returns an iterable of the dictionary’s keys.

-

dict.items() - this returns an iterable of the dictionary’s (key,value) pairs.

But why would we need to iterate over a dictionary?

Our dataset has about 860 listings, suppose we wanted to display the properties of all these on our website, it wouldn’t make sense to write the same markup 860 times. It would be efficient to dynamically render the data using a loop.

Let’s iterate over job2 using a for-loop using all the three methods. Furthermore we’ll use the csv module to read our csv-formatted data in to a list of dictionaries, then we’ll iterate through all the dictionaries and print out the keys and values.

# Iterating through the dictionary itself

for x in job2:

print(x) # prints the keys of job2

# Using keys()

for key in job2.keys():

print(key) # prints the keys of job2

# Using values()

for val in job2.values():

print(val) # prints the values of job2

# Dictionary iteration use case

import csv

with open('jobs.csv','r') as csv_file:

reader = csv.DictReader(csv_file)

for job in reader:

# Using items()

for key,val in job.items():

# Apply any additional processing

print(key, val) #print the keys and values of each job

-

First, we loop through the dictionary as it is. This is similar in output to stepping through the job2.keys() iterable.

-

Secondly, we iterate through job2.values() while printing out the value.

-

Finally, we step through the list of dictionaries, and for each one, loop through the keys and values simultaneously. We include both key and value in the for-loop constructor since job.items() yields a tuple of key and value during each iteration. We can now apply any kind of operation to our data at this point. Our implementation simply prints out the pair at each step.

7. Sorting

Borrowing from our description of dictionaries earlier, this data type is meant to be unordered, and doesn’t come with the sorting functionality baked in. Calling the sorted() function and passing it a dictionary only returns a list of the keys in a sorted order, since the dictionary is an iterable of its keys.

If we use the items() iterable we could sort the items of our dictionary as we please. However, this doesn’t give us our original dictionary, but a list of key-value tuples in a sorted order.

Say we wanted to display the job details in the above example in alphabetical order, We would need to alter our iteration to give sorted results. Lets walk through the example again an see how we would achieve that functionality.

with open('jobs.csv','r') as csv_file:

reader = csv.DictReader(csv_file)

for job in reader:

# Using sorted() to sort a dictionary's items on the keys

for key,val in sorted(job.items(),key=lambda item:item[0]):

# Apply any additional processing

print(key, val) #print the keys and values of each job

-

In this example we use python’s inbuilt sorted() function which takes in an iterable (our dictionary’s items).

-

The key argument of the sorted()function instructs sorted() to use the value at index 0 for sorting. This named argument points to a lambda function which takes in an item, say (“a”, “b”) and returns the value at the item’s first index, in this case “a”. Similarly, to sort by the values, we use index 1 instead of index 0.

Other Methods

Dictionaries have other methods that could be used on demand. To read up further on these, please consult the python documentation. Here are some other useful methods:

-

pop(key,default) - deletes the key key and returns it, or returns an optional default when the key doesn’t exist.

-

copy() - returns a shallow copy of the original. This shallow copy has similar references to the original, and not copies of the original’s items.

-

setdefault(key,default) - returns the value of key if in the dictionary, or sets the new key with an optional default as its value then returns the value.

Speeding Up your Code

Dictionary unpacking can greatly speed up our code. It involves destructuring a dictionary into individual keyword arguments with values. This is especially useful for cases that involve supplying multiple keyword arguments, for example in function calls. To implement this functionality we use the iterable unpacking operator (**).

What if we needed Job objects to work with, instead of dictionaries? We shouldn’t have to do some heavy lifting to get our data reorganized in to objects. Let’s see how we could translate our dictionaries into objects, by again tweaking our previous code.

#Define a Job Class

class Job:

def __init__(self,

title="Job Title",

location="Job Location",

job_type="Job Type",

employer="Job Employer",

category="Job Category",):

self.title = title

self.location = location

self.job_type = job_type

self.employer = employer

self.category = category

def __str__(self):

return self.title

# Creating a job object without unpacking

Job("Marketing & Business Development Manager","Mombasa","Full Time",

"KUSCCO Limited (Kenya Union of Savings & Credit Co-operatives Limited)",

"Marketing & Communications")

with open('jobs.csv','r') as csv_file:

reader = csv.DictReader(csv_file)

for job in reader:

# Creating a job object with unpacking

Job(**job)

- To instantiate a new Job object, traditionally, we would need to pass in all the required arguments. However, with unpacking, we just pass in a dictionary with the ** operator before it. The operator unpacks the dictionary in to an arbitrary number of named arguments. This approach is much cleaner and involves less code.

8. Anti-patterns: Wrong usage

Compared to lists and tuples, dictionaries take up more space in memory, since they need to store both the key and value, as opposed to just values.

-

Therefore, dictionaries should only be used in cases where we have associative data, that would lose meaning if stored in lists, or any other sequenced data type.

-

Dictionaries are mutable, hence not suitable for storing data than shouldn’t be modified in place.

-

Since dictionaries are unordered, it would not be sensible to store strictly arranged data in them. A possible candidate data type for this scenario would be the OrderedDict from the collections module. An OrderedDict is a subclass of the regular dict class, with the advantage of tracking the order in which keys were added.

-

Dictionaries are well-designed to let us find a value instantly without necessarily having to search through the entire collection, hence we should not use loops for such an operation.

# How not to search for a value and return it

key_i_need = "location"

target = ""

for key in job2:

if key == key_i_need:

target = job2[key]

# How to search efficiently

target = job2.get("location")

We have a variable key_i_need containing the key we want to search for. We have used a for loop to traverse the collection, comparing the key at each step with our variable. If we get a match, we assign that key’s value to the variable target. This is the wrong approach. We should instead use get(), and pass it the desired key.

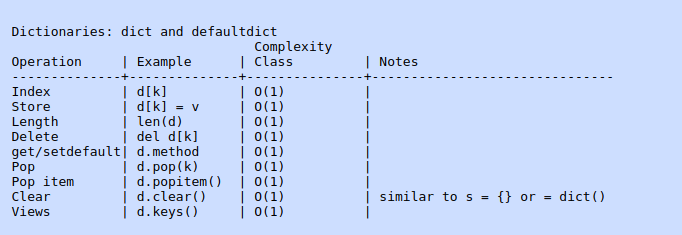

Performance Trade-offs

Dictionary operations are heavily optimized in python, especially since they’re also extensively used within the language. For instance, members of a class are internally stored in dictionaries.

Most dictionary operations have a time complexity of O(1) — implying that the operations run in constant time relative to the size of the dictionary. This simply means that the operation only runs once irregardless of the dictionary size. Creating a dictionary runs in a linear time of O(N), where “N” is the number of key-value pairs. Similarly, all iterations run in O(N) since the loop has to run N times.

Conclusion

Dictionaries come in very handy for regular python usage. They are suitable for use with unordered data that relies on relations. Caution should however be exercised to ensure we do not use dictionaries in the wrong way and end up slowing down execution of our code. For further reading please refer to the official python documentation on mapping types.